For decades, the country has approached child care financing as a binary choice: parents pay what they can, and government steps in only for those with the lowest incomes. The result is a system that leaves millions of working families without help, employers without a reliable workforce, and child care providers operating on razor-thin margins.

The Tri-Share child care model offers a different way forward—not as a final answer, but as an important experiment in how we might rethink responsibility for financing child care. At its core, the Tri-Share model splits the cost of child care three ways:

- Parents contribute a more affordable share;

- Employers contribute directly to support their workforce; and

- Government fills the remaining gap.

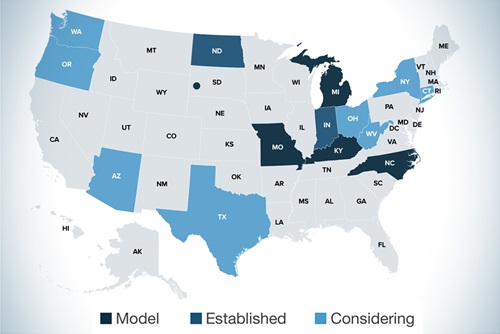

This structure is now operating in multiple states and localities, including Michigan, Kentucky, North Carolina, Missouri, and others.

Read the Buffett Institute's new Tri-Share report.

While each state’s implementation differs, the underlying premise is the same: child care is not solely a family issue, nor is it solely a public assistance program—it is a shared economic responsibility.

That framing alone is a meaningful shift. Policymakers and advocates alike should pay attention.

Tri-Share does not replace subsidies, Head Start, or universal approaches—but it fills a critical gap that advocates have long struggled to address. It serves families the current system leaves behind.

States that have modeled, implemented, or are considering Tri-Share programs

States that have modeled, implemented, or are considering Tri-Share programsMost Tri-Share participants are working families who earn too much to qualify for child care subsidies, but far too little to comfortably afford market-rate care. These families are often invisible in policy debates, even though they make up a large share of the workforce.

Tri-Share acknowledges a reality advocates know well: eligibility cliffs do not reflect real financial need. By smoothing costs rather than cutting families off, Tri-Share creates a more realistic pathway to affordability.

It Stabilizes Child Care Providers

From an early childhood perspective, one of the most compelling features of Tri-Share is its impact on providers. Payments are more predictable, enrollment is more stable, and providers are not forced to discount tuition or rely solely on high-income families to survive. This matters because supply cannot grow without financial stability. Tri-Share doesn’t just help parents afford care—it helps providers stay open.

It Engages Employers as True Partners

For years, child care advocates have argued that employers benefit from child care, but rarely help pay for it. Tri-Share tests what happens when employers move beyond symbolic support and contribute financially.

Early evidence suggests that employers participate because they recognize that child care reduces employee absenteeism and turnover; improves recruitment and retention; and allows employers to support workers without running their own child care programs.

It Reframes Child Care as Economic Infrastructure

Perhaps most importantly, Tri-Share reframes child care as part of the broader economy—not a social service on the margins. The model aligns child care policy with workforce development, economic growth, and labor force participation. This framing resonates with legislators who may not respond to traditional child care arguments but do respond to workforce shortages and economic competitiveness.

Why a Federal Pilot Is the Next Logical Step

A bipartisan bill was recently introduced in Congress. H.R. 6312, “Tri-Share Child Care Pilot of 2025,” would:

- Test the model across varied labor markets, including rural and low-density areas

- Evaluate different employer contribution structures and incentives

- Examine impacts on provider stability and wages

- Identify how Tri-Share can complement—not compete with—existing subsidy systems

- Generate the evidence needed to inform long-term financing reform

Importantly, a federal pilot would create space to learn, refine, and assess where shared-responsibility financing works best—and where it doesn’t.

Tri-Share Is Not the End Game—It’s a Building Block

Advocates are right to insist on broader public investment in child care. Tri-Share does not replace that goal. But dismissing Tri-Share because it is not universal misses its value. Tri-Share helps answer questions the field has struggled with for years, questions a federal pilot can help answer.

The bottom line is this: Tri-Share should be viewed as a policy laboratory—one that offers practical lessons about shared responsibility, affordability, and sustainability. For advocates committed to building a stronger, more inclusive child care system, supporting a federal Tri-Share pilot is not a retreat from public responsibility. It is a strategic step toward a more realistic and resilient financing framework.

If the goal is to expand access, strengthen supply, and recognize child care as essential economic infrastructure, then Tri-Share deserves a place in the national conversation.

Linda Smith is the senior director of policy at the Buffett Institute, with a specific focus on military, rural, and Tribal child care, early childhood financing, and engaging the business community in child care initiatives nationwide.