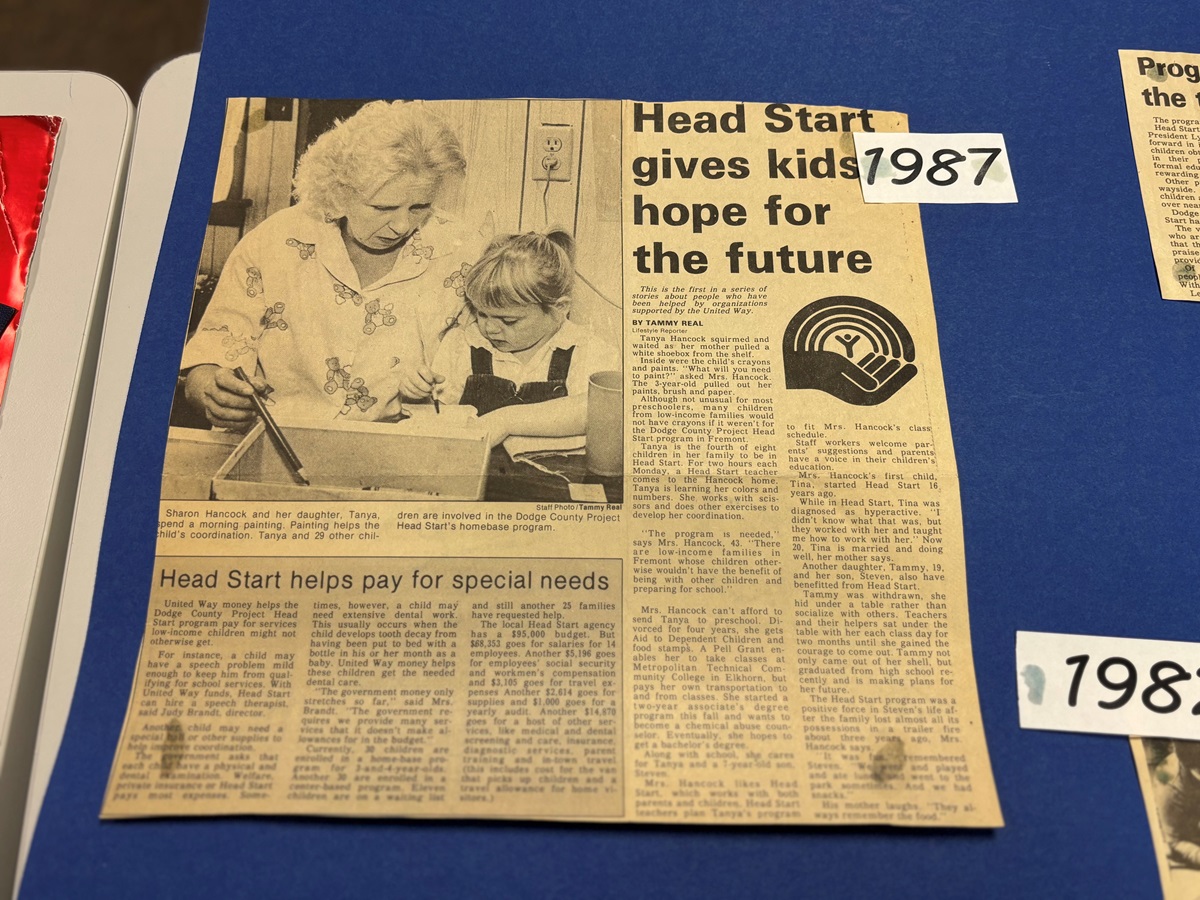

The headlines on the weathered, decades-old newspaper clippings speak to the promise of Head Start.

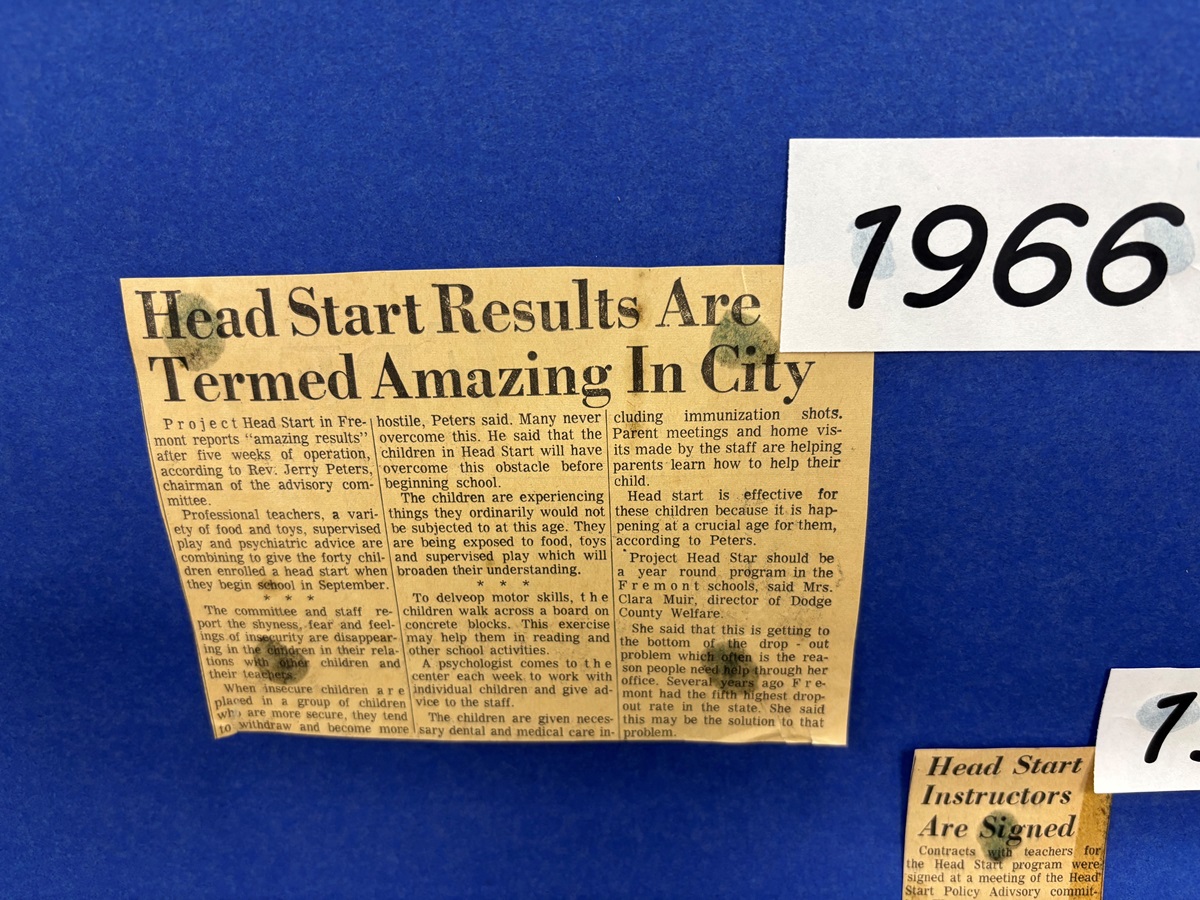

From 1966, just weeks after a Head Start program opened its doors in Dodge County, Nebraska: “Head Start results are termed amazing in city”

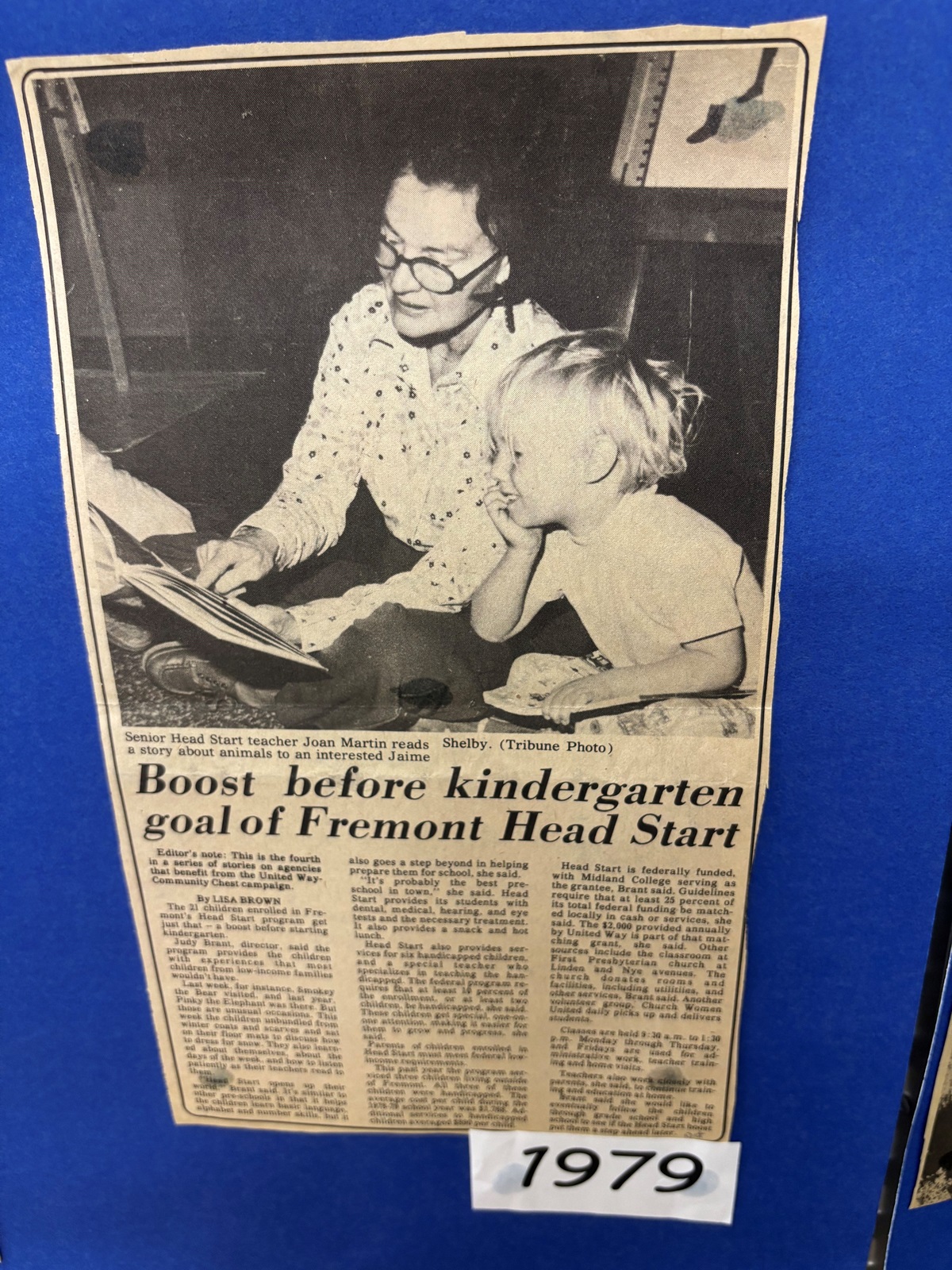

1979: “Boost before kindergarten goal of Fremont Head Start”

1986: “Head Start gives kids hope for the future”

2000: “Area preschoolers benefit from Head Start program”

Sixty years later, Shauna Roberts, the Dodge County Head Start parent, family, and community engagement specialist, feels confident that the program has lived up to its potential.

It has served an estimated 6,000 children and families in the Fremont area, about 40 miles northwest of Omaha. That’s 6,000 children and families who received quality early childhood education so parents could work and young children could be better prepared for school; 6,000 community members who were connected to much-needed services, like English classes, health care, or home visits.

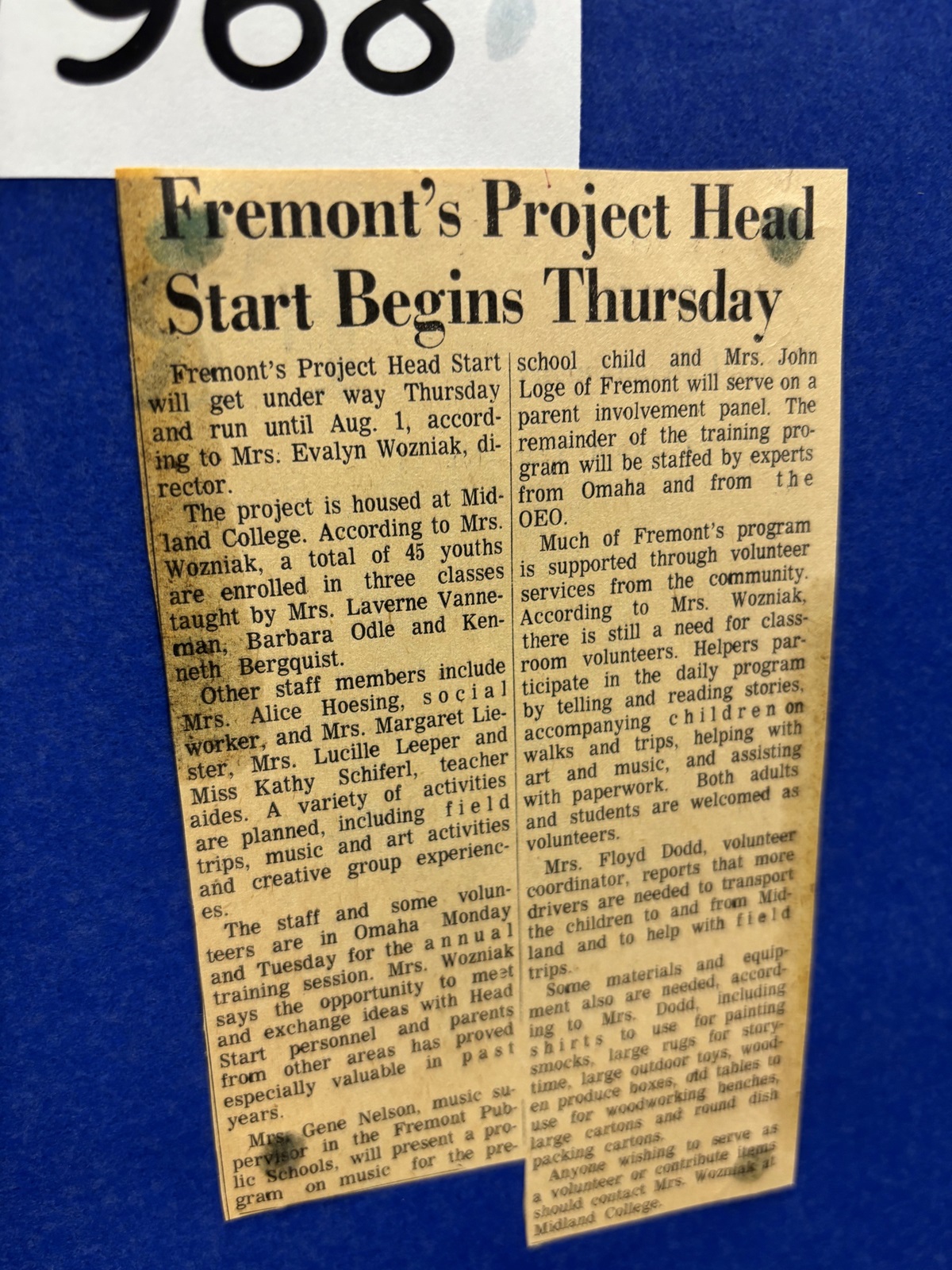

A National Movement Takes Root in Nebraska

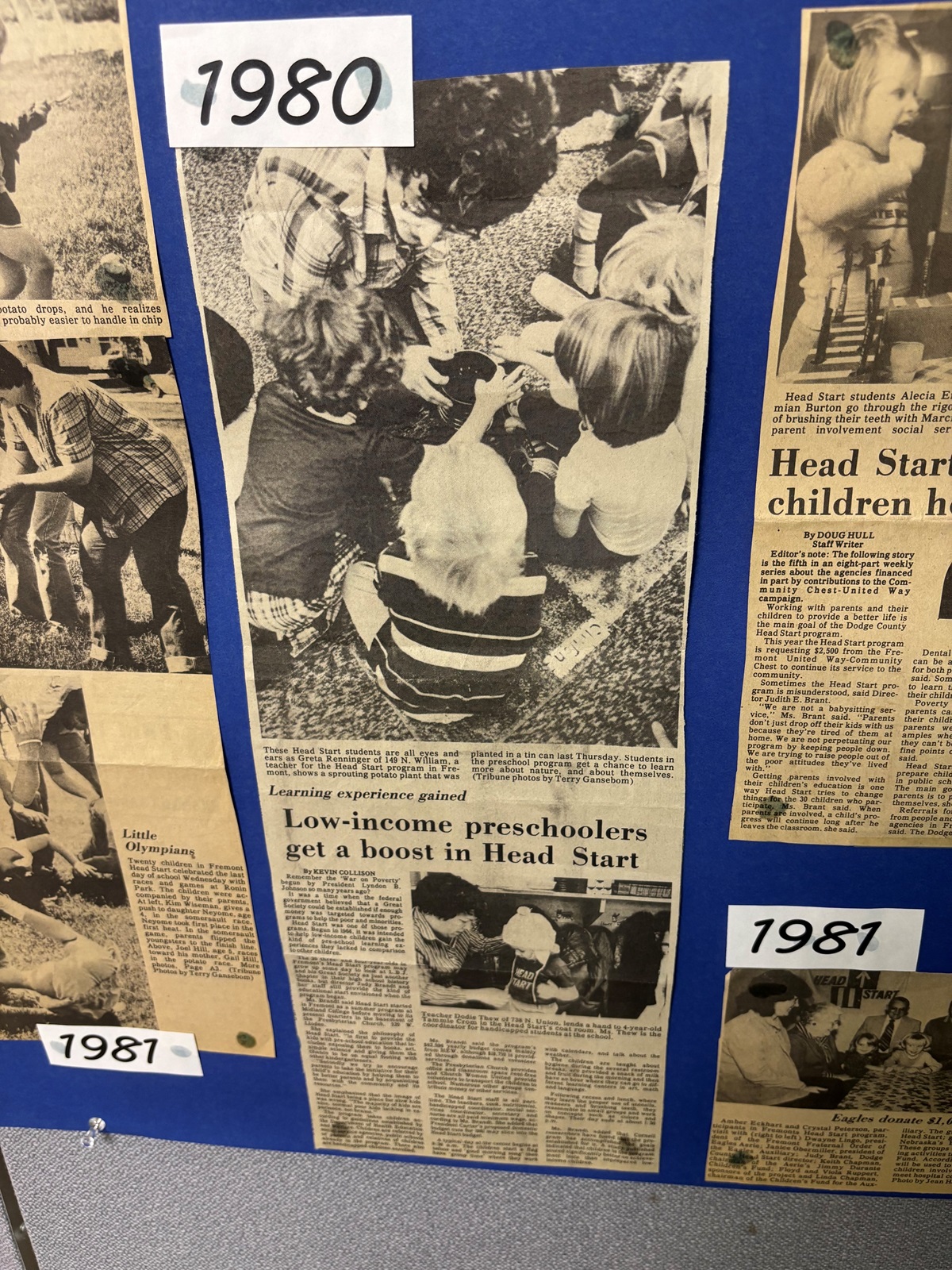

Dodge County received its first Head Start grant in 1965 to hold a six-week summer program on the campus of what is now Midland University. That’s the same year the national Head Start program started as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty.

“From the beginning, Head Start was designed as a comprehensive program to address the social, emotional, health, nutrition, and educational needs of young children living in poverty,” according to a 2024 Nebraska Head Start report from the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska.

Ed Zigler, the psychologist who helped design the program and is widely known as the “father of Head Start,” was for more than 20 years the mentor of Walter Gilliam, the Institute’s executive director. Gilliam directed the Edward Zigler Center in Child Development and Social Policy at Yale University from 2005 until 2023 when he came to the Institute.

“Dr. Zigler understood that we cannot truly care for a child without also carrying for that child’s family and community,” Gilliam said. “Often that means educational supports for the child, and often it also means helping the adults in their families find and keep gainful employment. It’s all about promoting family self-sufficiency.”

Across the country, Head Start programs are celebrating the 60th anniversary with balloons and cake at birthday parties and open houses.

At a coffee reception in Dodge County, community members and former teachers reminisced over old photos and toured classrooms.

The program currently enrolls nearly 80 children and families. That includes preschool students at its Fremont center and at Logan View Public Schools in nearby Hooper, Neb., and 15 Early Head Start home-based slots for pregnant mothers and young children up to age 3. There’s a waiting list each year.

Forty-one percent of Dodge County Head Start students receive special education or early intervention services. A number of students are English Language Learners. Head Start helps strengthen language development and acquisition so students can learn in both English and Spanish.

A Family-Centered Approach

“Our focus is the whole child and the whole family,” said Roberts, who is also a member of the Nebraska Early Childhood Workforce Leadership Cadre led by the Buffett Institute. “So, in addition to children having a safe, enriching environment to help support their development and prepare them for Kindergarten, we also provide services such as health screenings, nutritious meals, and support services.”

Head Start and its community partners connect families with job training, housing assistance, and parenting classes. Roberts, a child passenger safety technician, teaches parents how to properly install car seats.

And Head Start supporters tout bipartisan support and decades of results—healthier kids, higher high school graduation rates, more engaged parents.

“My daughter graduated second in a class of 376,” said Dawn Egr, a Dodge County Head Start parent and volunteer who now works there as a family service worker. “Head Start works. It’s an amazing program.”

Over the last six decades, 40 million children from birth to age 5 have attended Head Start programs in every state, on Tribal lands, and in U.S. territories like Puerto Rico and Guam. That includes kids who are in foster care or experiencing homelessness, as well as the children of migrant farmworkers.

The program is free for eligible families and often serves areas where child care is in short supply—55% of Head Start programs are in rural communities.

Funding Uncertainties

And yet, this year’s celebrations have been tempered by a temporary federal funding freeze and layoffs. Head Start funding remains in a federal budget proposal released this spring, and the administration has since seemed to retreat from eliminating the program altogether.

But uncertainty lingers, resulting in stress for staff and the families who rely on the program. In Nebraska, Montana, Michigan, and beyond, advocates have held rallies and launched letter-writing campaigns to drum up support.

If Head Start was eliminated nationwide, “800,000 of our more at-risk children would be affected,” Roberts said. “The impact of hundreds of thousands of parents not being able to work would be catastrophic. Efforts to strengthen families and support children contribute to long-term community success.”

The Power to Transform Families

Egr, the family service worker, has become one of Head Start’s biggest champions.

Her sister attended Head Start in the 1990s, and as a newly divorced single mother reentering the workforce, Egr enrolled her two youngest children in the Dodge County program.

Head Start wasn’t just a source of child care—it helped her build a new life.

She went back to school and after volunteering in the classroom, started working for Head Start as an aide, teacher, and family worker. She learned new skills for parenting her own kids, teaching them to identify and regulate their emotions. She received housing help through Habitat for Humanity.

“This program has given me a life that I don’t think I would have had,” Egr said. “Now I have an associate's degree. I'm a homeowner. I'm doing work in the community and representing the program and helping families. I've gone through the entire scope of the program itself.”

“I don't work at Head Start because I make great money,” she continued. “I'm here because I care about what I do. I'm here because I believe in it, and I know it works.”

Her past struggles help her relate to the families she works with now.

“I have been in similar situations,” she said. “I love the fact that a lot of feedback that I get is, ‘I don't feel judged here.’”

Head Start Vital to Community

Head Start operates under a federal-to-local model: funding is distributed to local organizations and agencies, including school districts, faith-based institutions, and nonprofits, that oversee and run programs. Midland University has been the Dodge County grant trustee since the program’s inception.

Rhonda Gdowski serves on the grantee board. A retired principal and administrator for Fremont Public Schools, she’s seen firsthand how quality early childhood education can help children make a smooth transition to Kindergarten.

It’s taken the Fremont area years to build its child care infrastructure, she said. If Head Start funding was cut, those spots could not be easily absorbed by existing programs.

“It would be a terrible setback for our community,” Gdowski said. “It would take away that comprehensive support system that families have. It impacts quality-of-life. It impacts our community. It impacts jobs."

Egr wants to see Head Start expand, not shrink.

“We are doing amazing things with these children, and the education is fluid,” she said. “There's no stagnation in Head Start. We are constantly growing, constantly changing, constantly improving, constantly reevaluating ways we can be better. Head Start is vital to building strong communities.”

Erin Duffy is the managing editor at the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska and writes about early childhood issues that affect children, families, educators, and communities. Previously, she spent more than a decade covering education stories and more for daily newspapers.