Policymakers in states lucky or prudent enough to have a budget surplus face a big decision: how will they spend those extra funds?

Some choose to fix up roads, cut taxes, or build back rainy-day reserves. Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont has proposed a strategic, long-term investment—a $300 million preschool endowment fund that would cut child care costs for families and create thousands of new preschool slots.

It’s a bid to make Connecticut “the most family-friendly" state in the nation, Lamont said, and a national leader in early childhood education.

To Walter Gilliam, it’s an investment that will pay dividends.

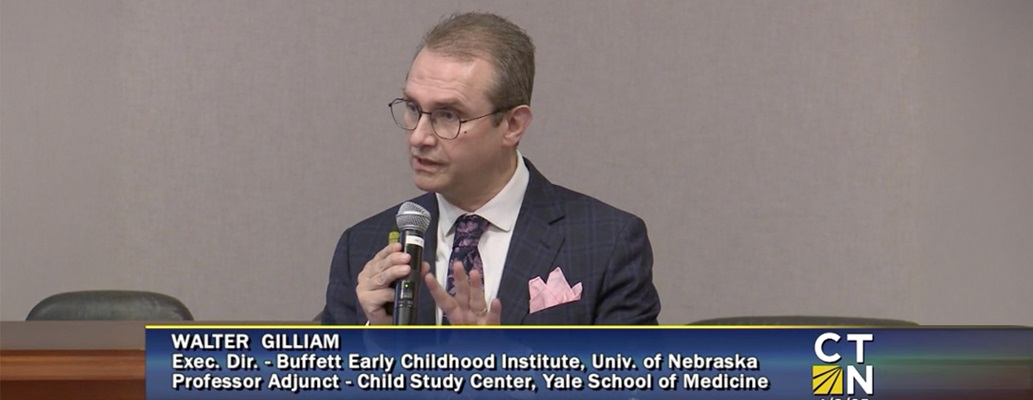

Gilliam is the executive director of the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska. He’s a former Yale University professor and Connecticut resident who gladly accepted an invitation to share his expertise at a packed early childhood roundtable at the State Capitol on April 8.

“Not every state is in a condition of surplus,” he said. “But most states are in a condition of surplus from time to time, and that this state would decide to invest its surplus in its future speaks a lot to not only the state, but to you, Governor, as a leader, so thank you."

The event was attended by early childhood educators and Connecticut legislators who will vote on the creation of the preschool endowment fund. The endowment would:

- Create 20,000 new, mixed-delivery preschool slots for 3- and 4-year-olds by 2032 and support infant-toddler care

- Make preschool free for families earning up to $100,000

- Cap preschool costs at $20/per day for families making between $100,000 and $150,000

- Grow each year with the goal of eventually reaching $2 billion

Gilliam and the Buffett Institute policy team provided key data for the proposed expansion by geomapping the child care need versus availability gap across all Connecticut communities. They found the state needs nearly 53,500 more child care spaces to fully serve children and families.

Walter Gilliam (far right) with early childhood leaders in Connecticut

Walter Gilliam (far right) with early childhood leaders in ConnecticutGilliam also highlighted studies showing the long-term effects of quality early childhood education and emphasized the need to expand access to child care while also increasing the pay of early educators. They make an average hourly wage of $17.50 in Connecticut, just a few cents more than lifeguards, fast food cooks, and amusement park attendants.

“If there was one thing that really we could invest in to make sure our preschool programs are high-quality, it would be investing in the adults that are in that room every single day with those children,” Gilliam said. “And primarily that means paying them well."

There is a domino effect. Better working conditions and pay for early educators can reduce turnover. That means more child care slots for families, which benefits businesses who need reliable workers.

“We know that families are often deciding between paying for child care or having one parent leave the workforce,” said Connecticut Lt. Gov. Susan Bysiewicz. “And we know when that happens that it’s usually the woman that does that. That shortchanges families, and that shortchanges the workforce. We need many more people in our workforce to grow our economy.”

Gilliam pointed to a recent study by economists at Yale’s Tobin Center for Economic Policy, a key partner of the Buffett Institute. It compared the earnings of New Haven, Conn. parents whose children were randomly selected to attend a free, all-day PreKindergarten program and those whose children did not.

The PreK parents worked 13 more hours per week and pocketed nearly $12,000 extra each year in increased pay and decreased out-of-pocket costs. They didn’t have to call out of work because they didn’t have child care. They didn’t have to scale back their hours to avoid losing a child care subsidy.

“$12,000 keeps people out of poverty,” Gilliam said. “$12,000 keeps people employed. $12,000 keeps businesses open.”

And, beyond the dollars and cents, quality early childhood education can set children up for success in the form of increased high school graduation rates, better health outcomes, and fewer school suspensions.

Gilliam hopes more states follow Connecticut’s lead to dedicate more funding to its youngest learners and recognize child care as the valuable infrastructure it is.

Besides, he asks, “What could be more valuable to invest in than our children?”

Erin Duffy is the managing editor at the Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska and writes about early childhood issues that affect children, families, educators, and communities. Previously, she spent more than a decade covering education stories and more for daily newspapers.